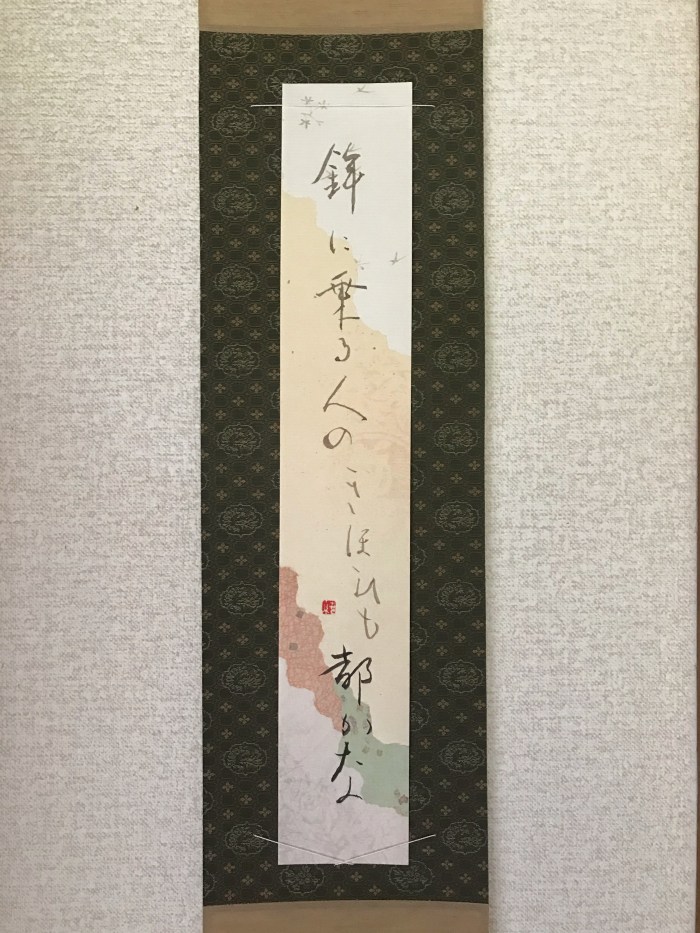

鉾に乗る人のきほひも都かな

(hoko ni noru hito no kioi mo miyako kana)

the pride of those on the floats

the elegance of the old capital

– Kikaku

Tanzaku (短冊) in calligraphy are vertically-oriented paper on which one writes waka (和歌 – Japanese poems) like this haiku, in which the 17th-century poet Takarai Kikaku (1661-1707), a cosmopolitan Edo (Tokyo) resident, admires the elegance of Kyoto and its famous Gion Festival. Hanging the tanzaku in my room—practicing the poem in kana calligraphy, choosing the paper, and purchasing a simple scroll—enhanced my own first experience of Kyoto’s month-long festival, which origins date back to the 9th century.

Kikaku’s mention of hoko (鉾 – halberd) refers to the grand parade, in which large, iconic yamaboko—elaborately decorated wooden yama (山 – mountain) and hoko floats (characterized by their long halberds more than 20 meters high), each with its unique names, histories, and traditions—make a slow, festive procession through central Kyoto. Having repeatedly practiced the character for hoko (鉾), I came across beautiful versions of the character while viewing the floats during the days and evening festivities next to the lit up floats leading up the day of the grand parade, like this one below (left), engraved on a wheel spoke of the Kikusuihoko (菊水鉾).

Some Kyoto-ites told me that they rarely attend the parade itself to avoid the tourist crowds, choosing to enjoy their own annual festival traditions. I happily joined the crowds and marveled at the procession of floats led by the Naginatahoko, with its flute-players, stately decorations, and large wooden wheels, with its namesake sword (halberd) extending high towards the midsummer sun.